|

Carousel carvings

are now a treasured art form, an active focus of preservationists,

museums, historians and collectors. It is hard to imagine that

carousel operators once trashed their wooden horses and menagerie

animals, burying or burning them in favor of homely, lower

maintenance aluminum castings. And nobody seemed to care. A number

of factors coincided to create a revolution of consciousness. One of

those elements was the Flying Horses catalog.

|

The first shot in

the revolution was fired by New York City historian Frederick Fried

in 1964. His

A Pictorial History of the Carousel

chronicled

the robust development of carousel manufacture in the U.S., giving

identity and artistic stature to such formerly anonymous carvers as

Charles Looff, Daniel Muller, Salvatore Cernigliaro and Marcus

Charles Illions. Fried’s scholarship also conferred stature and

encouragement to legions of closet carousel fans who discovered they

were no longer alone. |

|

Jo was one of those

fans, though she was much less isolated than most; she had a

lifelong motivation and a five year jump start into outreach and

research prior to Fried’s contribution. The image of her beloved

horses, turned to cinders by the overnight conflagration of the Long

Beach, CA, Looff machine, had burned as an unquenchable flame into

her ten-year-old soul. That smoldering trauma was both quenched and

rekindled when Rol presented Jo with a little horse for their second

wedding anniversary in 1959. Jo scoured the informational wasteland

that summer trying to find any clue to the origins of wooden horses.

She learned eventually that their horse was German but that,

contrary to popular myth, most of the carvings in this country were

not. The most interesting merry-go- rounds, with the most

diverse and creative styles of carving, were made in the U.S.A. But

where, and by whom?

The answers came in

the book. More answers and intriguing new questions emerged

from an exciting 1966 visit to Fred and Mary Fried in their

Manhattan townhouse. Thanks to the book, Jo and Rol had already

developed a particular interest in M.C. Illions. Now they learned

that Illions’ son, Rudy, lived a stone’s throw from Rolling Hills in

Ocean Park, California. They sought Rudy out at his Looff carousel

in Pacific Ocean Park. He was distrustful of their intense interest

at first. Carousel fans and carousel families were equally estranged

back then, sort of like townies and carnies. “What makes these kids

want to pry into our family business?”

|

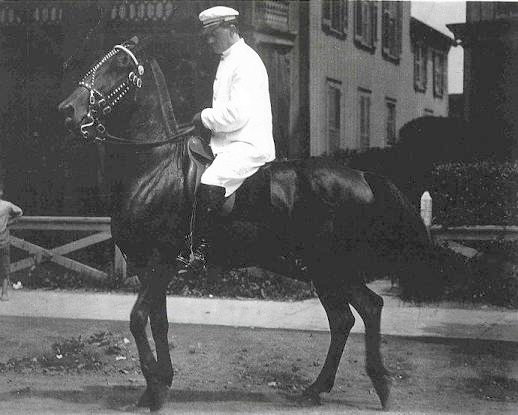

M.C. Illions on his horse "Bob". Illions

favorite was used for both racing and carriage. |

|

The mutual trust

and respect that emerged during the repeated visits with Rudy

Illions, then with his family and soon with his younger brother,

Barney, became typical of other alliances that emerged in the

carousel revolution: “Cerney” (Cernigliaro) and his daughter,

Marguerite, and, later, Bill and Marion Dentzel. These alliances

helped to restore dignity and pride in an artistic and cultural

heritage which had become obscured and even demeaned over time. |

Three generations of Illions: Rudy, grandson

Phil

and son Joe. Barney Center.

Rolling Hills, April 1, 1973. |

The young couple’s

quest to find an Illions horse for sale led them in 1969 to Marianne

Stevens, a no-longer-closeted fan in Roswell, New Mexico, who had

tracked down and purchased a group of fire-damaged horses from the

Illions Coney Island Boardwalk machine (the site eventually occupied

by the Flushing Meadows-bound Stubbmann carousel). They struck no

deal but the relationship struck oil. Jo and Marianne would get

together and pore over hundreds of photographs, learning to identify

almost any carousel figure by the subtle hallmarks of individual

carver styles. Those photo flash cards came from the travels of

Marianne’s friend Gray Tuttle, a South Carolina carousel operator

and dealer.

By 1970 this small

group of carousel afficionados was poised for direct assault on the

wasteland of public indifference. But each knew of only a few others

who could share the cause. There was no organizing medium, no

rallying cry, no roll to call. Enter the Flying Horses.

In the early spring

of 1970 Jim Wells, an antique band organ dealer in Fairfax, VA,

advertised some carousel horses for sale in Amusement Business

magazine. He claimed they were Illions, though Jo couldn’t quite

recognize the sample photo he sent of a particularly handsome horse

with a “needle” nose, deeply rippled mane and alertly pricked ears

(the flash cards had not discovered that rare, early Feltman style,

nor was it evident in the Fried “bible”). Whatever it might be, Jo

fell in love with it. Armed with a newly-arrived tax refund Rol flew

overnight to meet Jim on April 18, leaving Jo, excited and envious,

minding the home front with the four young children.

|

The sample/signature horse at Jim Wells' (in

front of a Stubbmann organ). |

Jim proved to be an engaging and persuasive

salesman. He advised Rol to check out the

former World’s Fair carousel in Flushing Meadows to verify the

concordance with his stock. The whirlwind shuttle to New York made

Rol a believer. And Jim’s horses, despite their sometimes-shattered

condition and the dingy environs of their semi-trailer stables,

suddenly shone with a new luster. Here was the chance to buy not

just one Illions horse, but dozens of them! And a bunch of Looff

carvings, to boot. Rol scrounged around for additional funds and

bought the lot.

|

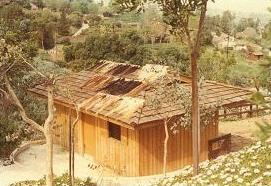

The arrival of a

Bekins van full of blanketed horses caused quite a stir in the rural

suburb of Rolling Hills, or at least the brush fire did. Under

ordinary circumstances 50 horses would have remained out of public

awareness, all spread out to be washed and inspected in the hollow

beyond a long, steep driveway. But suddenly the brushy hillside

directly across the canyon crackled into roaring flame. The fire

dispatcher Jo phoned in alarm insisted on listing the Summit’s

address, despite Jo’s passionate attempts to direct the response to

the street on the other side. Sure enough, the engines clogged the

street and fire crews grunted up the driveway with bulging hoses,

only to find a bizarre but tranquil horse laundry. Their hasty

turnaround ran counter to the tide of neighbors streaming up the

drive, equally unprepared for the surreal scene at the top. |

The fire |

|

After the fire (Jo holding

Sheri along with neighbors)

|

After the fire was

quenched and all the looky-loos had dispersed, there finally was

time to go back to inspecting the carvings, released now from their

years of accumulated grime. Rol noticed a mysterious pattern on the

off-side saddle blankets of some of the Feltman horses, little

nubbins of something distorting the thick smoothness of the

overlying paint. The bumps turned out to be hinges and latches for

hidden interior access doors, which Rol could open only when he

carefully chipped the margins free of dozens of layers of paint.

|

Inside were

treasures of the past, an unintended time capsule of the fabulous Feltman. There were scraps of ancient sandpaper and whole pages of

the New York World from 1902, Indian head pennies and an 1896

dime, Bonomo candy wrappers, paper bunting-wrapped canes and lots of

confetti from long-forgotten Mardi-Gras. And there were clues to the

reason behind these secret panels: some contained porcelain sockets

and Edison carbon filament bulbs. Apparently Charles Feltman had

hoped to extend his new-fangled, personally generated illumination

into the horses themselves, shining out through the portals of the

large, unmirrored jewels. But the Summits found no evidence that the

sockets had ever been wired.

|

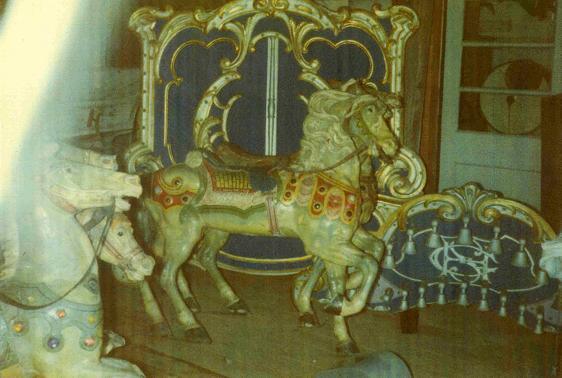

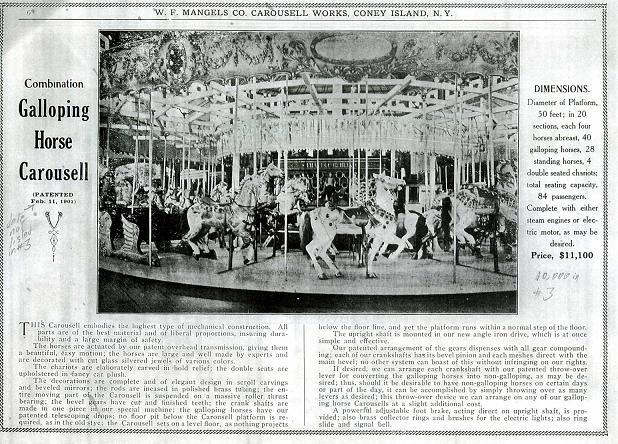

Feltman carousel in

Mangels catalog #4. The center horse is shown in the

Flying Horses Catalog #F105. |

|

Of course, the

fledgling county psychiatrist and his stay-at-home spouse

could afford space and capital expenditure to keep only a few of

their favorites among the 50 horses, so the couple set out to found

an enterprise, Flying Horses, to develop a market for what

they would have to share of their extraordinary wares. The

remarkable quality and provenance of those carvings deserved an

educated, appreciative clientele, something of an oxymoron in

those prerevolutionary days (the earlier flood of new recruits was

now barely a trickle since Fred Fried’s manifesto had passed out of

print). And if Jo and Rol couldn’t recognize a Feltman-style

Illions, who could?

The immediate task

was to more fully research the Illions/Coney Island

saga and to impart the exciting story to potential customers.

Far-flung buyers would need good pictures and accurate descriptions

to authorize the cumbersome process of crating and shipping a

hundred pound pig in a poke. The few existing dealers mailed

mimeographed lists and Polaroid snapshots to promote their familiar,

more popular brands (Dentzel, Looff, Philadelphia Toboggan). The

Summits’ more innovative outreach would require an integrated

publication: a catalog, one with a story, with pictures, and

with a stated mission of carousel appreciation, restoration and

conservation.

The story research

created the pleasant obligation to schedule more lengthy, more

focused interviews with Rudy and Barney Illions. They and

their families warmed to the task, entertaining the Summits in their

homes, reconstructing long lost memories and mapping the amusement

landscape of Coney. They brought out family photos and company

archives. As the text developed it was family reviewed and critiqued

for tone and balance. Edo McCullough, author of that colorful book,

Good Old Coney Island, whom Rol had met on his epochal visit

to Virginia, phoned and mailed contributions, including rare gifts

of historic brochures and artifacts.

The pictures

emerged from an amateurish, impromptu studio Rol had crammed into

one corner of the two-car garage, already packed with close ranks of

gorgeous horses. One by one, the horses to be sold were rotated into

place against an old black bedspread and caught in the glare of

three opposing floodlights. The low-tech production required pasting

the Polaroid images on 8-by-11 black cardboard, with labeling

supplied by strips of Dymo tape. All that black was too much for the

basic print shop, so the photo masters had to be taken to a deluxe

printer. The three oldest Summit children formed a production line

to edge-dip each of the three photo pages into a pan of glue and

insert them into fully a thousand collated and stapled editions.

|

Jo’s cover drawing

depicted her favorite “keeper”, the love-at-first-sight teaser that

had sent Rol flying to Fairfax. That sample horse turned into the

“Signature Horse” with a remarkable development: upon

inspecting the interior with a flashlight through the newly discovered lightbulb-access

panel, Rol discovered that the carver had scrawled “M. Illions” on

the top board before the body was glued together. |

So was born the

first-ever actual catalog of collectable carousel horses and

supplies. Once the glue was dry the little books were mailed out to

the growing number of previously anonymous merry-go-round mavens who

were sending a dollar (refundable with any order) in response to a

tiny display ad in Sunset magazine. Those strangest of books

went out on that strangest of evenings: Halloween.

The

Sunset ad put the Summits in touch with more than 1200

interested fans. So much for the roll to call to revive the

revolution! But who would call it? One of the new contacts

emerged to rally the troops. Barbara Charles actually lived in one

of the apartments above the Santa Monica pier carousel (the one

featured in the movie, The Sting). She phoned and requested a

meeting to help plan her projected national tour in search of

operating carousels. That trip inspired Barbara to become a vocal

missionary for carousel research and preservation. It also

established an unprecedented photographic and textual archive,

forming the basis for Barbara’s subsequent articles in such

prestigious journals as the Smithsonian (July, 1972).

William Dentzel II

was another of the catalog contacts. His namesake uncle was

“Hobby-Horse Bill”, son of Gustav Dentzel, the grand patriarch of

American carousel manufacture. Bill’s father had left the

Philadelphia factory and moved west, eventually to become mayor of

Beverly Hills, CA, also becoming intellectually estranged from his

“carnival” origins. Bill took heart from meeting the Summits to

reestablish his carousel roots. He learned from Rol how to sharpen

chisels and set out to form a contemporary dynasty of carving

Dentzels.

Barbara and Fred

Fried hatched the idea, in November, 1972, of forming a national

organization. Fred secured the use of the Heritage Plantation in

Sandwich, MA, for the national get-together he proposed for the fall

of 1973. Fred’s designated organizing committee was that same

emergent circle of boosters: Barbara Charles, Marianne Stevens, Grey

and Judy Tuttle, Bill and Marion Dentzel and Rol and Jo Summit. The

first official meeting was in March, with the Frieds and Dentzels

assembled in the Summit living room and Barbara and Marianne on the

phone. Each kicked in $50 apiece for postage to reach some 1200

potential members (only 8 cents postage in those days), almost all

of whom were F.H. catalog contacts.

Over 200 people

assembled in Sandwich on October 20, 1973, as charter members of the

National Carousel Roundtable, later to be named the

National Carousel Association. Bill Dentzel was elected

as chairman, with other founders from the organizing committee

taking key roles for support and development. The N.C.A. went on to

become a worldwide leader in carousel research and conservation.

Within less than a

decade, Fred Fried’s 1964 opening shot had mobilized his chiefs of

staff, who recruited loyal troops and marched into national

attention; the revolution at Sandwich was noted not only by Time

magazine but also in My Weekly Reader, which assured school

children all over America that adults cared about merry-go-rounds,

too.

Jo and Rol

fulfilled their catalog promise to revive Fried’s out-of-print epic

and to become a source for exotic restoration supplies: eyes,

jewels, gold leaf, wooden tails and natural horsehair tails, hide

and all. Rol spent weekends down hill and downwind in the “Flying

Horses Skunk Works”, skinning, trimming, washing and pickling

hundreds of tails for whole carousels and individual restorers. The

catalog and its The Carousels of Coney Island became

benchmarks in the new trend toward researching, preserving

and restoring carved wooden carousels rather than deserting and

despising their rich cultural and artistic heritage and abandoning

them to inevitable extinction.

|

Suzy and Rol in the "Skunkworks"

(washing, combing out prior to curing an alum-brine solution) |

Tails drying

February, 1971

|

|

So the

Flying Horses catalog provided a

defining moment in the renaissance of merry-go-round mentality. The

redemption of the orphaned remnants of the Feltman Carousel

rekindled some of the same kind of excitement early visitors to

Coney Island must have felt in discovering the revolutionary Illions

original, as well as the delight inspired in later generations by

its World’s Fair offspring. Such is the nature of the carousel

revolution. |

Rol & Jo

Summit

|